|

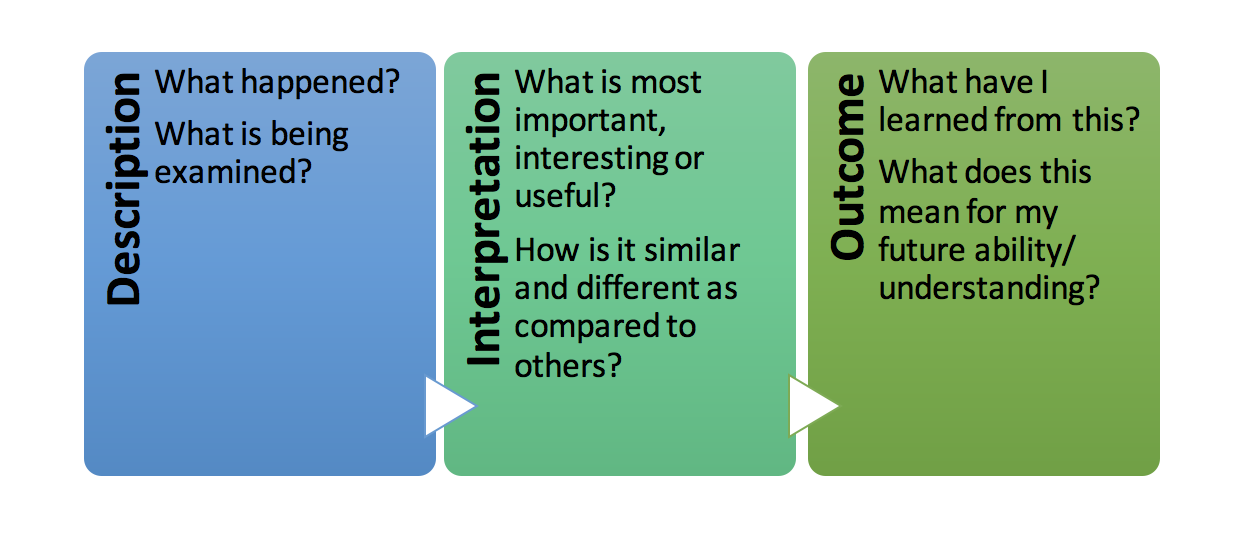

Years before I went back to school to get a Master's degree in Leadership & Policy Studies, a colleague of mine told me that she had been asked by her faculty advisor as she completed her Master's degree what her one big take-away had been. Her response, she said, had been that it's important to read the foreword in a book. In all honesty, I didn't see the value in the behavior she recommended at the time of our conversation; it wasn't until years later that I discovered the wisdom in her words. Something else that exchange did for me, though, was to serve as a prompt during my own graduate studies, and, upon earning my Master's degree several years later, I identified my own big take-away: There is great value in the process of reflection. Since I began teaching occupational therapy students, I have been interested in how, when, and why they reflect and how that impacts their learning. Over time, what I have noted is that there is great variability in the methods of instruction in and in the expectations and evaluation of reflective writing. In fact, “the widespread espousal of reflection as a key to effective learning has meant that its meaning is assumed to be obvious to all” (James & Brookfield, 2014, p. 26); however, in the midst of the multitude of methods of delivery and expectations associated with this teaching and learning technique, only infrequently are students provided with structured and distinct instruction about the process of reflective writing (James, 2007). Several months ago, I came across an article by Martin Hampton in the Department for Curriculum and Quality Enhancement at the University of Portsmouth (n.d.) that provides a detailed breakdown the components of a high quality reflection. In the article, reflective writing is defined as evidence of reflective thinking and, in the context of academics, described as having three components:

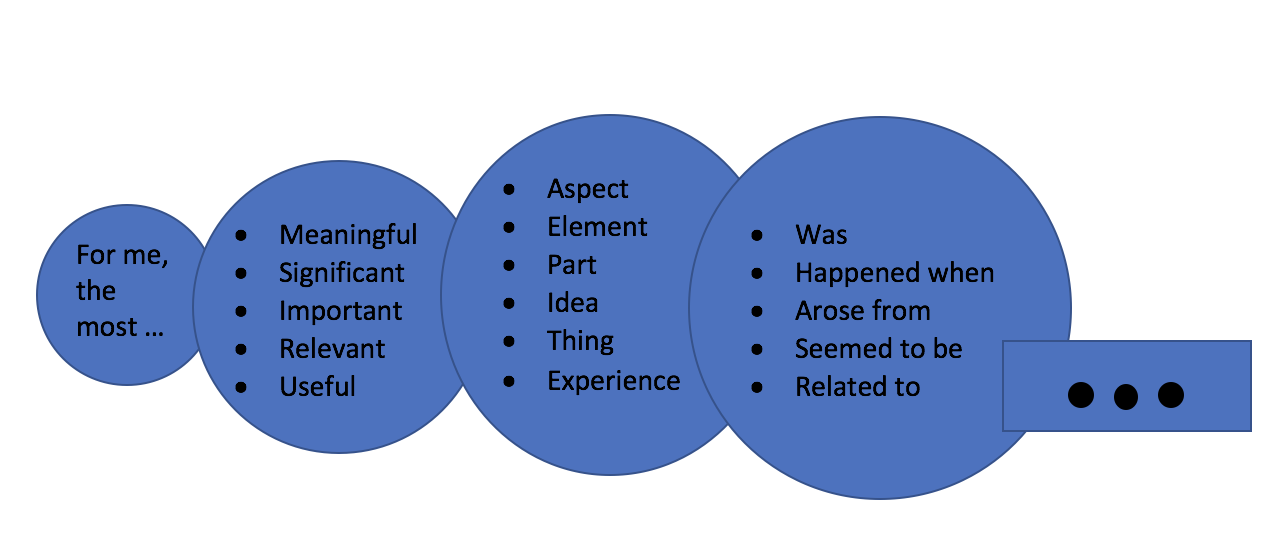

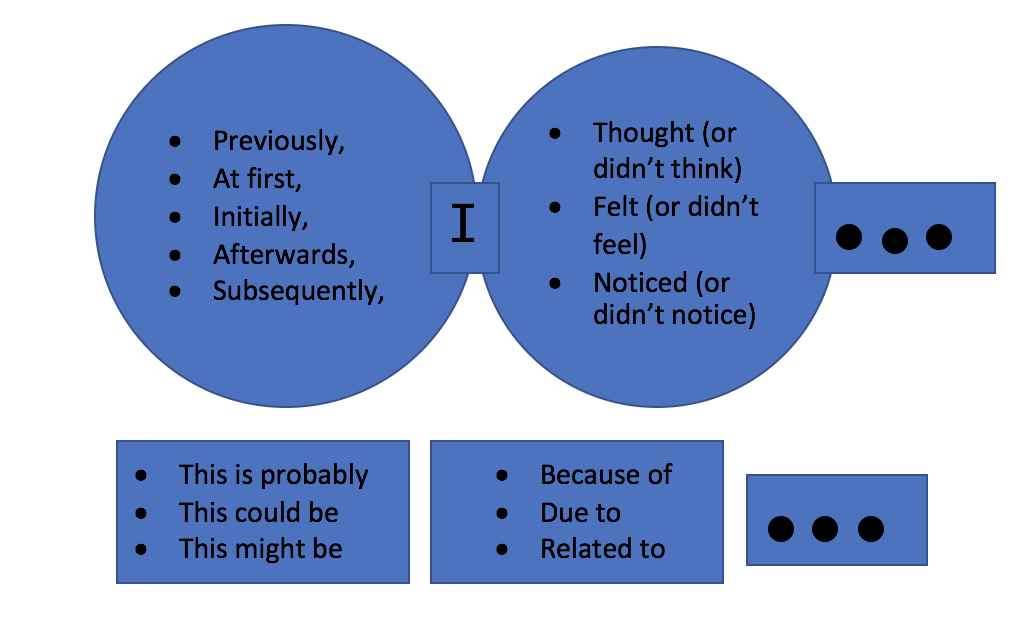

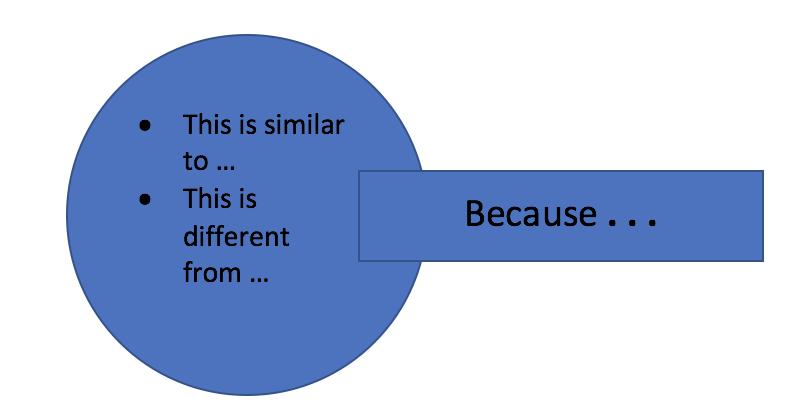

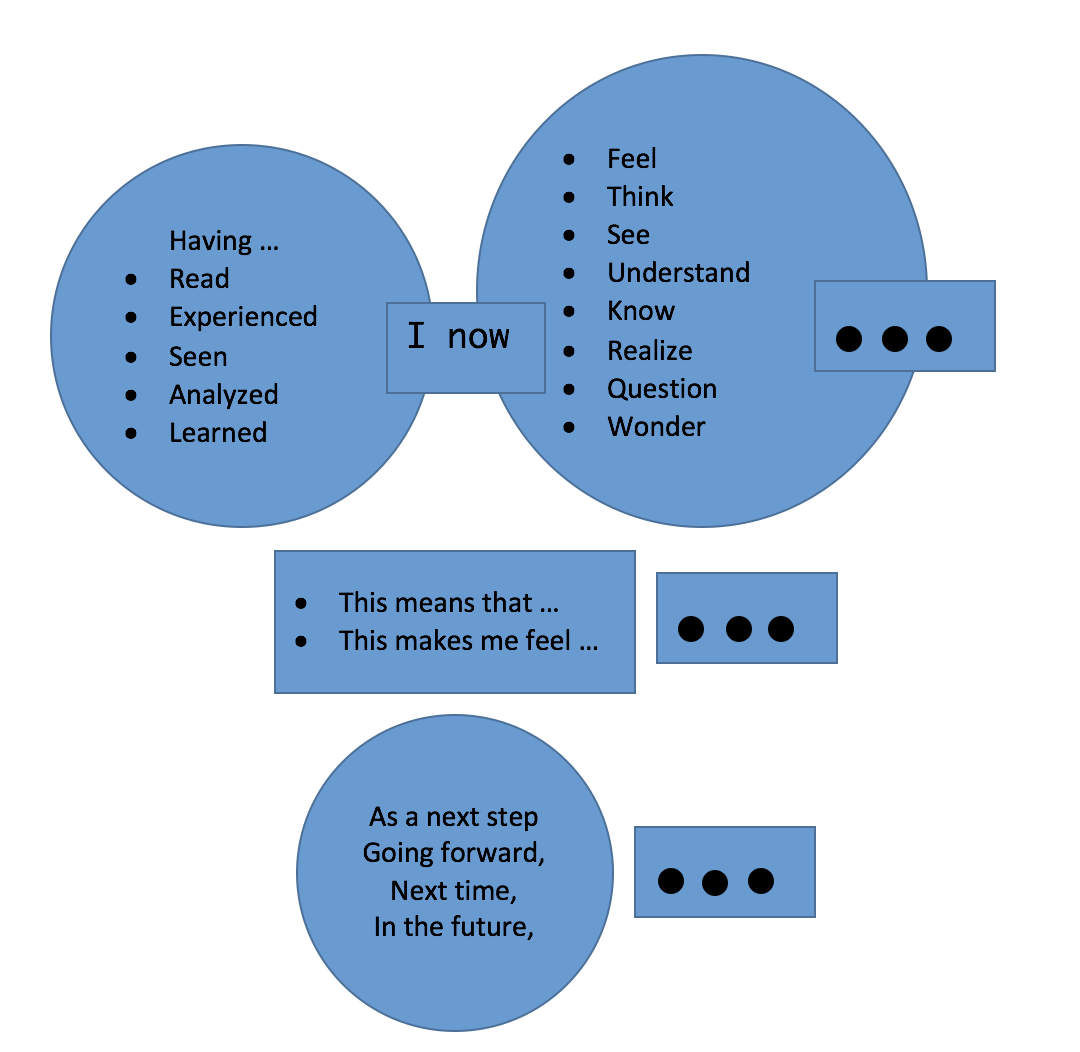

Reflective writing is thus more personal than other kinds of academic writing. We all think reflectively in everyday life, but perhaps not to the same depth as that expected in good reflective writing at [a] university level." ~Martin Hampton When a situation or assignment calls for carefully structured reflective writing, it may be helpful to think of questions that related to each of the of three parts: Reflection is an exploration and an explanation of events -- not just a description [or summary] of them. Genuinely reflective writing often involves 'revealing' anxieties [and/or other emotions], errors and weaknesses, as well as strengths and weaknesses. It is often useful to 'reflect forward' to the future as well as 'reflecting back' on the past." ~Martin Hampton Following is a series of diagrams that serve as a breakdown of the possibilities for wording - or a DISSECTION of a REFLECTION. Each of the 3 big rectangles represents one of the major components, and the phrases in the other shapes are meant to serve as prompts in the writing process. Please note that this is just one way to structure reflective writing; there are other ways, and you may be required or you may choose to follow a different model. Please remember, though, regardless of the format you choose, that there is great value in reflection ... and that, like many other things in life, oftentimes what you get out of this process is directly related to what you put into it. References

Hampton, M. (n.d.) Reflective writing: A basic introduction. University of Portsmouth: Department for Curriculum and Quality Enhancement. Retrieved from www.port.ac.uk/ask James, A., and Brookfield, S. D. (2014). Engaging Imagination: Helping Students Become Creative and Reflective Thinkers. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. James, A. (2007). Reflection revisited: Perceptions of reflective practice in learning and teaching. Art, Design, & Communication in Higher Education, 5(3), 179-196. Wald, H. S., Borkan, J. M., Taylor, J. S., Anthony, D., and Reis, S. P. (2012). Fostering and evaluating reflective capacity in medical education: Developing the REFLECT rubric for assessing reflective writing. Academic Medicine, 87(1), 41-50.

2 Comments

Earlier this week, a screening of the film Unrest was held for students and faculty in occupational therapy education programs. The film, a documentary by Jennifer Brea, tells the story of several individuals diagnosed with myalgic encephalomyelitis, or ME, which is often referred to as Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. The film has won awards at Sundance and other film festivals. I first learned about Unrest about a year ago through conversations on Twitter, and I reached out through the film's website to inquire about hosting a screening on campus. A few months ago, I got an email from a member of the screening team with whom I corresponded to work out the details leading up to the screening event. In addition to the occupational therapy students on the campus where I teach, an invitation to attend the screening was also extended to occupational therapy assistant students at another institution in the area, and several of those students attended the event as well. After the film was shown, I asked the students to consider sharing what their big take-away was, if anything had surprised or really struck them from the film, and how what they saw might have impacted their ideas as a future OT practitioner. Several students made comments about how disheartening and frustrating is it that the stigma surrounding conditions like ME serves as such a huge barrier in our society, both for the individuals diagnosed and their caregivers. The resiliency of the people in the film impacted the viewing audience at the screening, as did their apparent drive for purpose and meaningful connection, both of which are intertwined with occupations and the philosophy of OT. We agreed that there were a number of memorable quotes in the film, including the comment Jen made about there being such a difference between being alive and living - again, another point that really resonates with occupational engagement. One student noticed that there was a line in the movie about spoons, a concept that relates back to The Spoon Theory, which we discussed in a course the students took last spring. Finally, the comment was made that it isn't just those diagnosed with ME that may feel disconnected, stressed, or depleted: Caregivers are also likely to experience these things and many other emotions, and this is an area in which there seems to be a place for occupational therapy to play a role. A couple of images from the documentary that students said will stick with them as they continue to work towards entering the field of occupational therapy come from the scene in which Omar is struggling to get Jen back into their house after the rally and the footage of the shoes from the protest. ... one of the things that I've learned ... is how resilient humans are, and that, when we face challenges that we think will break us, we can find within ourselves resources that we didn't know we had." ~Jen Brea That [pre-illness] life is gone, but here I have this new one, and I have to fight for it." ~Jen Brea, in Unrest In conclusion, the OT students and faculty enjoyed learning about ME and related topics through the viewing of this documentary, and we recommend that all healthcare practitioners and students watch the film.

|

AuthorStephanie Lancaster, EdD, OTR/L, ATP is an occupational therapist with over 30 years of clinical experience. As an associate professor, Stephanie trumpets the value of teaching and practicing in the field of OT in an "out loud" manner. Archives

December 2021

Categories |

| The Outloud OT |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed